Liberalism, a Faltering Religion

Do people care about democracy? Would they be fine with democratic fascism?

The 2024 election is the latest sign confirming that liberal democracy is in crisis—both as an ideology and as a form of government. One major factor in the crisis is that American so-called “liberals,” when they think about “liberalism" at all, tend to think of it negatively. This is part of a greater trend conflating democracy, liberalism, and perhaps a third thing, “rights,” in the popular consciousness. I don’t think it’s possible to buttress liberal democracy without a successful rehabilitation of liberalism, and that requires getting clear about what all these different things are, and what they might become.

What Are We/You Fighting for Exactly?

“Love Letter,” a story story from 2020 by George Saunders, has been circulating in the wake of Trump’s return to power. David Sedaris read the letter on a podcast before the recent election as a kind of warning. In the story, a grandfather writes to his young adult grandchild from some time in the near future where the country is governed by an oppressive, fascist regime. He laments that he couldn’t muster sufficient outrage during the “critical period” at someone “so clownish.” Taking the cherished political system for granted, he preferred to work on jigsaw puzzles in quiet rather than “drop everything in defense” of what the buffoon gleefully began tearing down.

I admit that I do not identify at all with the grandfather and his implied refrain that he ‘should have done more.’ The grandfather indeed asks the most important question without really answering it:

“What would you have had me do? What would you have done? I know what you will say: you would have fought. But how? How would you have fought?”

One gets the sense that those who emphathized with the grandfather’s regret imagine loud vocal opposition in cyberspace. But the idea that speaking out on social media is an effective means of “fighting back,” so popular in 2016, has lost its luster. The sense that “outrage” is sufficient, or even necessary, to effective political opposition is no longer widely shared.

, for example, who sympathizes with much in the story, writes about her misgivings about the value of “genuine outrage.”The grandfather does not say “I didn’t vote for him.” Voting is not what matters in the story. The implication even runs in the opposite direction: liberalism must be defended from the voters.1 It is a moral duty to “fight” against majoritarian outcomes whenever they threaten cherished rights.

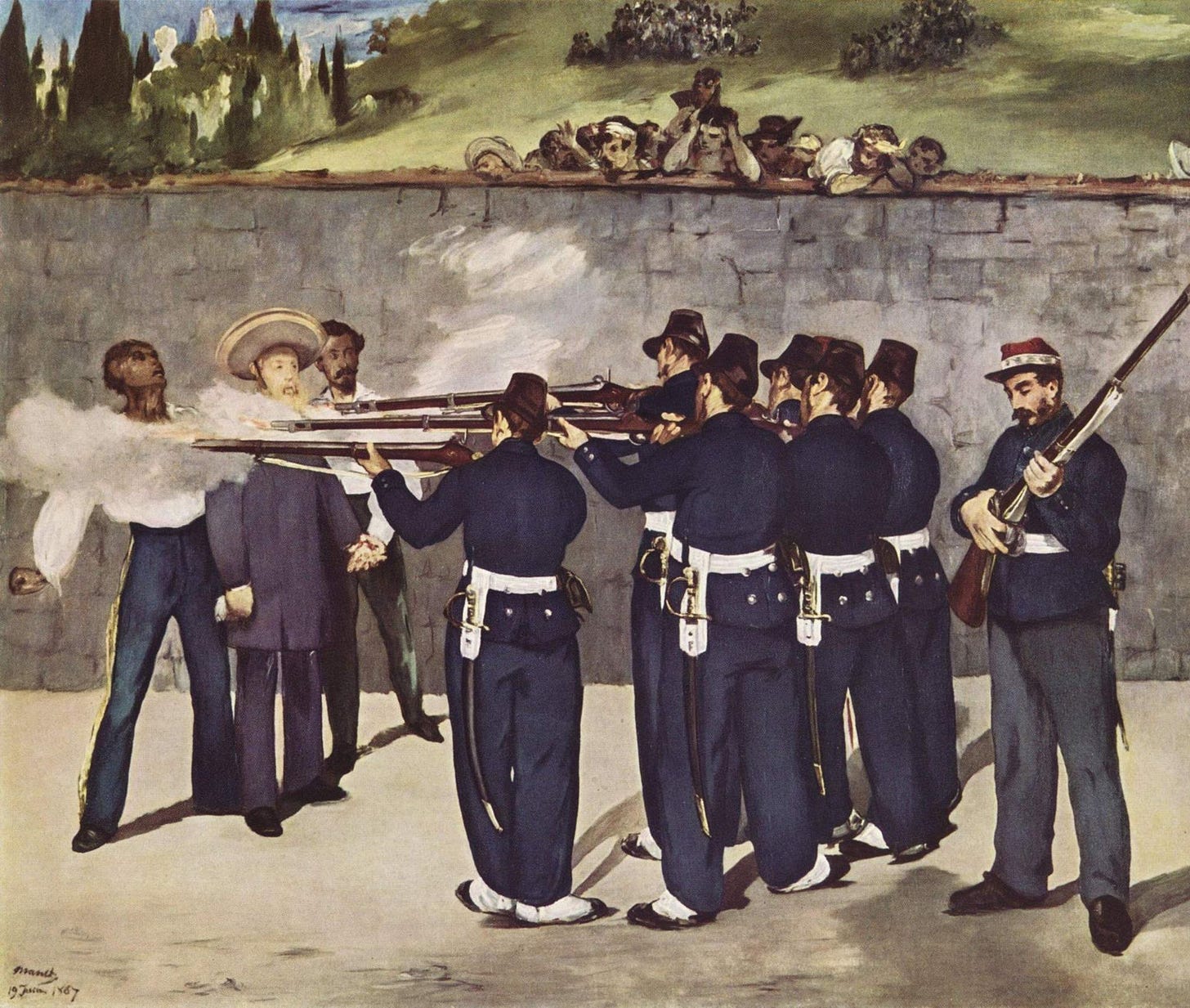

Most of the Democratic messaging in the final weeks of the election focused on Trump as a fascist threat to “democracy.” Rather than just saying what most people who were concerned about a Trump victory were really afraid of—the erosion of liberalism and its attendant anti-majoritarian rights—they focused on branding Trump as undemocratic, as a “dictator.” In the Democratic imaginary, fascism is the dark, dictatorial “other” to American liberal democracy—not so much the will of the people, as the intervention of some outside force. Trump might have won the popular vote, but that doesn’t mean he has a mandate to overturn liberal norms. People didn’t vote for that, they only voted for more money in their pocketbooks …

The Saunders story highlights how legitimacy is never just a matter of voting for the liberal democrat. Even voting in every election might not be enough to morally exculpate you from responsibility for the outcome of those elections. Yes, you voted, but did you “fight” for your side, even after you lost? (What does this mean exactly?)

The Untwining of Liberalism and Democracy

Back in 2009, Peter Thiel said that he “no longer believe[s] that freedom and democracy are compatible.” His quixotic solution was for freedom-loving libertarians to flee democracy for things like seasteading. Since the 2016 US election, many have observed that democratic liberalism is actually pretty fragile.

, for example, writes in The People Vs. Democracy that democratic liberalism is under threat, worldwide, on both sides:on one side, undemocratic liberalism—rule by the bureaucratic administrative state and technocrats, including unelected judges

on the other, democratic illiberalism—the rise of populist parties headed by figures like Trump and Orban, who want to tear down the institutions and flirt with fascism

In Mounk’s view democracy and liberalism are mutually dependent on each other in order to secure stability, prosperity, and freedom. These two pillars seem to be drifting apart, and he is worried that democratic liberalism is not a self-legitimating regime. Its legitimacy might instead be premised upon a public track amongst voters of "keep[ing] the peace and swell[ing] their pocketbooks, not because they hold a deep commitment to its most fundamental principles”2

agrees with Mounk that democracy and liberalism are conceptually coming apart, worldwide, and argues that in some sense we must decide which is more important. But rather than electing libertarianism, like Thiel, or some kind of technocracy, he champions a “democratic minimalism.” He thinks that democracy’s promise of self-government is much more important for long-term stability, at least so long as democracy means the peaceful transition of power. Liberalism’s reliance on Rawlsian “public reason” in order to settle disputes relegates religion too much to the sidelines, thwarting democratic movements premised on core religious commitments, particularly in the Middle East. The US should focus on supporting regimes that are committed to free and fair elections and the continuous peaceful transition of power. Rather than focusing on open markets and individual rights, democracies should be allowed to make the “wrong” choice, at least in American eyes, by electing, for example, Islamist governments, at least insofar as they are committed to holding elections in the future in which they might be ousted by a fair vote.One of the more surprising graphs from Mounk’s book shows poll results asking people whether they believe it is “essential” to live in a democracy:

If only 29 percent of Millennials believe that living in a democracy is essential, and the trend holds for Gen Z, it is no surprise at all that Kamala’s messaging on the importance of “democracy” fell flat. Any number of things appear to take precedence: prosperity, individual freedom, egalitarianism, social justice, or religion, not to mention what Hobbes says is the primary concern—security.

“Liberalism,” meanwhile has come to seem like a dirty word for many, especially among younger generations. On the right it has come to signify the “left” in its entirety, evoking contempt in proportion to one’s provinciality. On the left it has become partly synonymous with “neoliberalism,” an epithet that roughly seems to mean “Capitalist” or “Clintonite,” depending on one’s level of sophistication.3 Some self-styled “heterodox” thinkers claim to be “classical liberals,” as a way of distinguishing themselves from modern heresy. There are also the post-liberals, like

and J.D. Vance, who view liberalism as a threat to “real” freedom.Liberalism and its subcategories, then, might be even more on the outs than “democracy,” among a diverse cast of educated groups and intellectuals. Few people are willing to openly criticize democracy per se, even if they don’t seem to value it very highly. Liberalism, on the other hand, has been the subject of increasingly withering attacks since the financial crisis of 2008.

recently published an article basically arguing that liberalism has already become the underdog in global politics. This echoes a long line of books about liberalism and its decline, some defending it and some accusing it of being self-abnegating. We seem to be a long way from 1992.Everyone is a Liberal and No One Wants to Be

Part of the incoherence of “social justice” or “wokeism” or whatever you want to call that broad family of shallow arguments and sentiments is its willingness to completely disavow “liberalism” as tainted despite constantly appealing to inherent “rights.” How does one ground these rights, especially if the very concept of the “human” looks suspiciously Eurocentric and racist, and “human rights” looks suspiciously like a colonialist justification for intervention and domination? Religion might offer one avenue for securing rights, by appealing to the dignity of the soul or equality under God. But this cannot do the work of justification for an inherently pluralistic cast of thought, committed to affirming all religious choices, and so committed to no metaphysics in particular.

More rigorous thinkers might insist that rights are socially constructed, and therefore socially negotiated. We don’t need to appeal to any particular form of transcendence, Catholic, Islamic, Hindu, or Mormon. Instead we can engage in political agonism and fight for our principles, simply because they are ours. But providing a space for discursive political struggle requires putting some principles beyond contestation: tolerance of disagreement, not putting into question our opponents’ rights to legitimately contest us, protecting freedom of expression and assembly.

It’s not clear that “rights” mean anything at all outside of some “minimalist liberalism.” We are back to a universalist credo of liberalism, which will inevitably offend some, and in some places might be democratically rejected.

Stanley Fish, once upon a time called the “Donald Trump of American academia,” basically rewrote an essay for the 2024 election that he had previously written nearly 30 years ago, called “Why We Can’t Just All Get Along.”4 The basic premise is liberals are like Satan, and religious integralists are like Adam. Fish is a Milton scholar, so he’s referring to the characters in Paradise Lost.

Liberals know by evidence. The religious know by faith. “But in fact on the level of epistemology both are the same.” Each requires an unfounded a priori commitment to even get thought off the ground.5 Even though liberals claim to operate without faith, always retaining an open mind that is changable in the face of evidence, they are nonetheless committed to broadmindedness, and are immovable on that point. For liberalism to remain liberalism, it must remain commited to a set of procedures that are not value neutral, and which necessitate excluding some views from the public square for lack of standing:

What is not allowed religion under the private public distinction is the freedom to win, the freedom not to be separate from the state, but to inform and shape its every action.

Fish’s theoretical framework has always had trouble accounting for persuasion. He often talks as if people just are a certain way, as though they were incapable of being or seeing any other way. Even if people do change their minds, it can’t be important, because we have no objective way of understanding how or why outside of our own limited epistemological framework.

How one views all of this depends on how one views the role of “ideas” writ broadly. What is the point of liberal democracy without the possibility of persuasion? If everyone is trapped in their own interpretative community, ala Fish, persuasion is insignificant, epiphenomenal, and we can just move straight to a simple tallying up of votes, no discussion required. All that matters from this perspective is whether the tally is accurate. A “free election,” with “free speech” and self-expression, is non-sensical because it doesn’t change anything.

But he gets important things right, including the serious threat that liberalism poses to mainstream Christian and Islam thought, not to mention political constellations like fascism and communism. It is becoming increasingly untenable to affirm a world view in which limitless diversity can be assembled around the table for rational discussion “in and through difference,” while disavowing the liberal preconditions that make such a thing thinkable in the first place. The contradictions are just too great. Hosts who invites brigands in for dinner naively court their own ruin.

This does not mean that we must return to “classical liberalism” as though such a thing really existed or we could turn back the clock. It does mean that moderates concerned about the rise of democratic illiberalism and leftists concerned about the rise of fascism need to recognize their mutual interest in preserving something like “public reason.”

For those on the left, concerned about marginalized voices, there should be honest reflection about how academic arguments that filter down into vulgar discourse and disparage “liberalism” are actually parasitic on disavowed liberal foundations. Games of intellectual two-step—where people claim that “liberalism” is so weighed down with historical baggage that it’s actually just bad, and then offer a new paradigm defined by tolerance of diversity but called something else—have played no small part in eroding the public norms that make such criticisms possible. Leftists have long viewed “liberal” norms as upholding the status quo and preventing change from the left, but this increasingly looks like cope for their inability to persuade the public.

Others, like the Democratic party, should recognize that floating signifiers like “democracy” just aren’t effective symbols for political cathexis anymore. Democracy and liberalism are not the same thing, and it might be necessary for anyone committed to both to provide spirited theoretical defenses for each. What do we mean by “democracy” and how committed to it are we? Is democracy worth having if people make the “wrong” choice? if the majority wants to get rid of substantive rights to autonomy and freedom?

Admittedly, this story was published in 2020, before Trump had won the popular vote. And if Trump had lost the popular vote but won the electoral college in the recent election, it seems likely that the tenor of the conversation would be markedly different.

p. 131.

Marxists have attempted a more specific definition of “neoliberalism,” centering on responses to stagflation beginning in the ‘70s.

has attempted to explain it as basically a misattribution that became a vibe.Terry Eagleton accuses Fish of writing the “same” book over and over. He is not alone among academics in doing this. And sometimes he makes good points.

See also a similar argument in Leo Strauss’ lecture on “Reason and Revelation.