Moral Progress and the Binding of Isaac

Is Abraham killing Isaac a nightmare or a dream come true?

The Akedah, the binding of Isaac in Genesis 22, is an old story. Like most stories from that time and place, it is told almost entirely without interiority. Terse words are spoken—by Abraham, by God, by Isaac, by God’s messengers—but there is no inkling of spiritual or emotional turmoil. Days of travel pass without comment, and the action is limited to the critical events. The last line says, simply: “And Abraham returned to his lads [i.e. servants/slaves], and they rose and went together to Beersheba, and Abraham dwelled in Beersheba.”1 Isaac is not mentioned.

Erich Auerbach emphasizes how little we are told in this story. Unlike the illuminating foregrounds and touching details found in Homeric epic, the Akedah, like much of the Hebrew Bible, tells us who the actors are, and what the goal is, but says little about about them, or even when the action is supposed to be taking place. It is a “bottle episode,” floating back and forth on the currents of mythic time, bringing its spare, out-of-joint message to those who live in history.

It is difficult to return to a naive reading of this story which has become so sedimented with layers of cultural meaning and interpretation. If we tried, what might strike us is how hard and unworkable are its lineaments. The first verse indicates that God “tested” Abraham, and by the end God has blessed him. But this adamantine kernel seems to raise more questions than it answers. It offers few points of interpretative purchase.

at has been grappling recently with the notion of moral progress and his fascination with the sublime. In a recent podcast with the two talked over the sublime terror in the Akedah, Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, and Kant’s notion of the sublime. Damir faults liberals for clinging to a “rationalist safety blanket” that allows them to explain away horror. Stories like the binding of Isaac can be deftly folded into narratives of moral progress about how we moderns are not like that anymore.2 Yet, in eliminating the fearsome demands of often vengeful gods, the disenchantment of the world seems to leave it sterile and lifeless. Some might even see the end of history in such a dead world.Of late, there appear to be signs of human life, red in tooth and claw. Fukuyama has postponed the end of history. Russia has invaded Ukraine. Azerbaijan has expelled the Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh. Violence is endemic across the arc from Yemen to Sudan. China seems to be planning for war with Taiwan. Israel is attempting to exterminate Hamas and Hezbollah.

The Akedah raises the spectre of a God who demands human sacrifice. The angelic messenger stays Abraham’s cleaver-hand, and a ram "caught in the thicket by its horns” is offered up instead of Isaac. But there is no indication in the text of the story that Abraham was particularly troubled by the demand to sacrifice his “only” beloved son, nor that this demand would have been seen as unusual by those who heard it. Even the purpose of the story is opaque. It tells us that Abraham is blessed, and establishes his position as the prime patriarch, the grandfather of Jacob-become-Israel. But the troubling role of human sacrifice in the story demands explanation, and there has been no shortage of interpreters.

Kierkegaard emphasizes the absurdity of the sacrifice, which amounts to an impossible demand. A loving God could not demand something which contravenes all human decency. Kierkegaard’s “paradox of faith” consists in the contradiction between ethical demands, rooted in human sociality, and the religious demands of God. Despite its absurdity, however, it is worth emphasizing that for Kierkegaard faith is always a faith in a loving, benevolent God. Kierkegaard projects onto Abraham a belief that God will retract his demand at the last moment, or failing that, resurrect his son.3 The Akedah is distinguishable from the story of Iphigenia, sacrificed by her father Agamemnon in order to propitiate the goddess Artemis, because Agamemnon is a tragic hero who acts for the greater good at great personal sacrifice—he must give up his daughter in order for his contingent of warriors to reach Troy. Agamemnon need not muster any unusual faith concerning the outcome. It is just a rational calculation, a quid pro quo. Abraham, in contrast, must act in the face of ineradicable uncertainty, and he must act entirely outside the bounds of human ethical norms. There is no explanation he could possibly offer to others for doing what he must, in faith, do. Yet he believes in the goodness of God.

Another strain of interpretation likens the testing in the Akedah to the main problem set forth in Plato’s Euthyphro: is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods? In other words, is God’s Law the law because it is good, independently of God, or is God’s law the law because it is what he wishes, and nothing more?

It is more than coincidental that the setting of the Euthyphro involves a conflict between father and son. Euthyphro runs into Socrates outside the “courthouse” where he is prosecuting his father for the unjust killing of a househould servant/slave. The dead servant was a “dependent” of Euthyphro’s. The father bound him and threw him in a ditch for drunkenly killing another household slave. Euthyphro took exception to this. Socrates asks him how he intends to prove to the jury that this was unjust, especially as it might seem that a son prosecuting his father for something he did to his own slaves might seem impious and unjust itself. Euthyphro points to the example of Zeus, “the best and most just of the gods” who “bound his father because he unjustly swallowed his sons.” If Zeus was pious and just in that case, then Euthyphro must be pious and just in his. But Socrates points out that the gods disagree about things. Zeus might agree with Euthyphro but Kronos might not. What actually makes something pious or impious?

The Euthyphro never comes to an answer on this question, though Socrates is frustrated with Euthyphro’s circular answer that the gods love what is pious, and the pious is what is dear to the gods. Most of Western, Christian thought has embraced the first horn of the dilemma, asserting that right and wrong are right and wrong independently of what anyone thinks, even God. God is omnibenevolent and so of course upholds the good. But the good is logically prior to God’s commands to avoid evil and seek the good. Islam, arguably, takes the other horn of the dilemma: submission to the divine will comes first, and God’s sovereignty is not to be questioned.4 What is particularly unnerving about the Akedah under this reading is the possibility that God himself might be a moral monster, at least in our eyes. Embracing the second horn of the dilemma forever puts morality beyond the reach of reason. Only revelation could reveal it, in all its radical contingency, to us. Moreover, there are hints glinting on the surface of the Akedah that suggest that God himself didn’t always know the outcome. He might have actually changed his mind.

Sometimes historicizing is a tactic for “explaining away” a text.5 In this case, adopting a source critical method of interpretation that looks towards the deep history of the text serves to deepen the story’s unnerving testament to an alien Weltanschauung that remains all too human. Yahweh and El(ohim), both names for the Hebrew God, have always existed uneasily alongside Molech, derived from the three letter semitic word mlk. This word is referenced in the Bible, usually suggesting a god who receives human sacrifice, as well as Ugaritic texts, and has also been found on Punic inscriptions in areas of Carthaginian settlement. Jon Levenson comes down on the side of the Bible in suggesting that the word probably referred to a god.6 Others suggest that it referred to a particular ritual of human sacrifice, perhaps in the form of a burnt offering, usually a child.

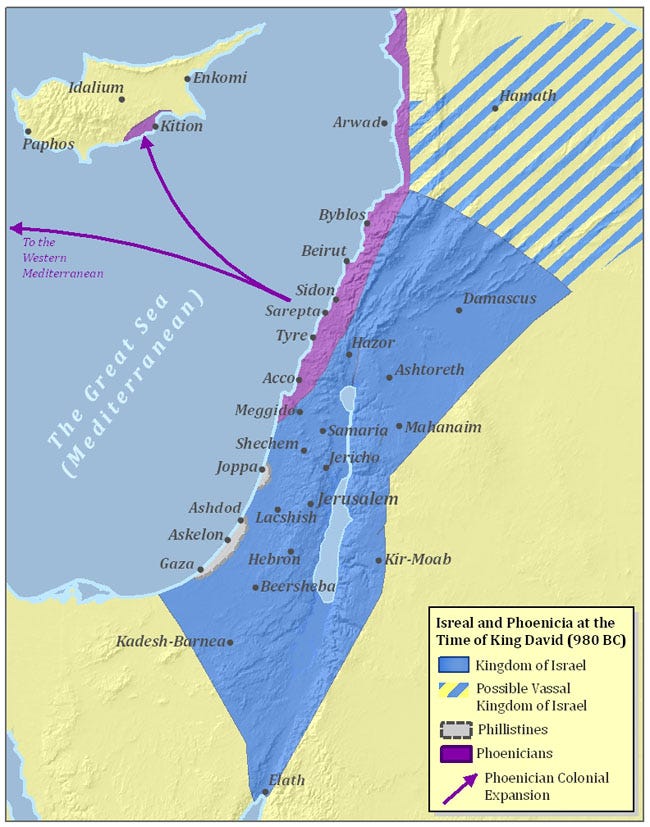

Both Levenson and María Eugenia Aubet emphasize that child sacrifice was primarily practiced by the elites: the royal family and the aristocracy. Many of the tophets, or Punic burial sites stretching across the Mediterranean from Carthage to Spain, contained hundreds or thousands of child bones, up to three years of age or even more.7 At least beginning around the seventh century BCE—coinciding with the Hebrew prophets like Jeremiah and Ezekiel who were vociferously opposed to human sacrifice—these tophets also contained animal bones, suggesting that poorer families might substitute an animal in place of a child.

There is no easy story of moral progress here, however. Human sacrifice appears to have become more popular as time went on, at least in the western Mediterranean, when Rome started to vie with Carthage for control of the Mediterranean.8 There is less archaelogical evidence for this resurgence of child sacrifice back east in the Phoenician homeland. J.C. Quinn has even suggested that Carthage was originally founded by a group of religious hard-liners who left Tyre, not unlike the Puritans leaving England.9 The Phoenician-Canaanite culture group, as pluralistic and fragmented as it was, seemed to share a belief that divine favor and good fortune could be purchased with blood. The more valuable the blood, the greater the favor that could be expected.

Some of the oldest layers of the Hebrew Bible are more or less explicit about divine claims on human life. Exodus 22:28-29 says quite clearly:

The first yield of your vats and the first yield of your grain you shall not delay to give. The firstborn of your sons you shall give to Me. Thus you shall do with your ox and your sheep: seven days it shall be with its mother; on the eighth day you shall give it to Me.

Levenson points out that the verb translated as “give” here is one associated with burnt offerings. The offering of the firstborn sons is placed right in the middle of a list of living objects that are offered up in sacrifice. Noscitur a sociis. It is hard, in other words, to read that “giving” as anything but sacrifice, even if there is a great temptation to explain it away. How could any community that offered up all its firstborn sons in burnt offerings sustain itself?10 Levenson therefore argues that this is evidence of a normative ideal in which sons can be given up as burnt offerings, but are sometimes redeemed by the offering of a substitute.

The Bible contains other stories of child sacrifice where its authors express no clear disapproval. Jephthah the Judge promises God that he will sacrifice the first thing he sees coming out of his door when he returns home if God will provide victory over the Ammonites.11 His daughter is the first to greet him. But despite his regret, he upholds his vow, and God seems to accept the sacrifice. Mesha, the King of Moab, sacrifices his son and heir on the city walls in order to turn the tide of battle against the Israelites.12 It does not seem to be in vain. It works.13

The prophets of the 8th-6th centuries BCE were very much opposed to human sacrifice. That they felt the need to oppose this at all suggests that it was still ongoing. But it seems like they also had to grapple with arguments that it was Yahweh himself who had demanded the sacrifices. Ezekiel, for example, speaking as a medium for God, tells the elders of Israel:

And I [i.e. God] on My part gave them statutes that were not good and laws through which they would not live. And I defiled them with their gifts when they passed every womb-breach in sacrifice, so that I might desolate them, so they might know that I am the Lord.14

The logic here is that God intentionally gave the Israelites bad laws that required child sacrifice so that they might be desolated, so that they would come to know and respect his divine sovereignty over them. Now, Ezekiel and others are calling them to reject the idolatrous sacrifices of humans, found, for example, in Exodus. God has changed his mind. Admittedly, it is more than a little unclear whether Ezekiel thought these “bad laws” were only bad now, or whether they were always bad. But could laws intended to desolate be good because they are God’s will? Would Ezekiel embrace the second horn of Euthyphro’s dilemma?

Tzemah Yoreh is a rabbi of a “humanistic” Jewish congregation who was something of a child prodigy in biblical studies and has a double PhD. He has written several books employing his own version of the Supplementary Hypothesis for critically examining the Biblical texts. In Why Abraham Murdered Isaac he claims that in the earliest layers of the Akedah Abraham actually does kill Isaac.15 The argument goes something like this:

The earliest layers of the story all refer to God as “Elohim,” the name employed by the original author(s) of the first five books of the Bible.

The E author(s) appears to have come from northern Israel.

There are several verses in the story that refer to God through the tetragrammaton YHWH. These were added at a later date by a Yahwist author, likely from southern Israel, representing the Davidic line of kings descended from Judah, son of Jacob/Israel.

If we peel away the verses added later, identifiable through various means, including reference to YHWH, we are left with the ancient story of Abraham, who sacrifices his son Isaac according to widely-held cultural norms, and returns from the mountain without him.

Jacob, therefore, cannot be the son of Isaac (who was sacrificed). Jacob was a northern Israelite hero, in the mold of other Levantine hero figures, who was reclaimed by the Yahwist southern Israelite author(s) as descending from Abraham through Isaac.

The Hebrew Bible as we have it today, then, revises the original story, recentering it on the tribes of Judah in the south, and retrojecting a sacrificial ram as substitute for Isaac.

The deeper we plunge into this historicizing narrative, the more unstable any notion of “moral progress” appears. If anything, it is Kierkegaard who starts to look like the Polyanna, unable to imagine a God who would trade in blood. Or perhaps even more unsettling, to imagine a moral universe in which the preservation of human life, let alone children’s lives, was nowhere near the highest good.

On a final note, we might consider adopting the viewpoint of Isaac. He was a grown man in the story. How could the elderly Abraham have bound him in the first place without his consent? The original story offers little insight on this matter. But Levenson outlines how in the Hellenistic period of the 2nd century BCE, Isaac became an exemplary figure for Jewish thinkers promoting a new martyrology. The Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes had issued laws requiring all Jews to eat pork and meat sacrified to idols, and persecuted them. In response, Jewish writers conjured up conversations between Isaac and Abraham as they headed up to the altar on the mountain. Isaac enthusiastically embraces his role as sacrifical offering:

Yet have I not been born into the world to be offered as a sacrifice to him who made me? Now my blessedness will be above that of all men, because there will be nothing like this; and about me future generations will be instructed and through me the peoples will understand that the Lord has made the soul of a man worthy to be a sacrifice.16

The nightmare of child sacrifice has been transmuted into glorious, even joyful, martyrdom.

Our historicist foray into the Akedah and related stories presents a variety of meanings that have come down to us, many of which are incompatible. If the naive reading of the Akedah reflects a sense of universal awe and terror in the face of inscrutable demands, a multilayered reading that integrates the millennia-long reception history of the text emphasizes the contingency of that meaning. For those who have eyes to see, the continual reworking of its meaning is visible in the text itself—the editing process that constructed the Hebrew Bible as it has come down to us.

It also clarifies how fear of nature or its gods often curdles into a submissive acceptance that arrogates meaning to “God’s Will”. Euthyphro’s dilemma has real stakes. If something is good simply because God wills it, we lose the ability to debate and determine the good through democratic discourse. Instead we get competing revelations, apparently impervious to argument.17

At the same time, the long hermeneutical view on offer here puts into relief the “liberal” vision that elevates “human rights” and the preservation of life as the supreme good. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights enumerates a series of non-hierarchical rights that might very well conflict. Which right is supreme?18 Is there really nothing more important than preserving life? Is there nothing worth dying for? The kind of people smug enough to dismiss the Akedah as ancient barbarism, overcome long ago, are the same kind of people who simplify the world by dividing it into oppressed and oppressors—two groups that we can tell apart by weighing the suffering on each side—as though nothing in this world was worth suffering for.

My brackets. Translations from Robert Alter’s The Hebrew Bible.

"Let us go further. We let Isaac be really sacrificed. Abraham believed. He did not believe that some day he would be blessed in the beyond, but that he would be happy here in the world. God could give him a new Isaac, could recall to life him who had been sacrificed. He believed by virtue of the absurd; for all human reckoning had long since ceased to function." (p. 15)

This is obviously a complicated question, and we would be better speaking of Islams and Christianities, plural. Some Islamic theologians have certainly taken the first horn of the dilemma. Some Christians, like William of Ockham, have taken the opposite one, asserting a divine command theory wherein God’s will is primary and morality is secondary. The question is unavoidably bound up in the legitimacy of sovereignty and reason’s competing claim to universally knowable constraints on sovereignty.

It is hard to tell what exactly Kierkegaard thinks, except that God would never command evil.

says that he would say “It’s a stupid question, you should be listening to God’s call. That you would even ask it shows you are not a serious person.”pp. 18-19.

The word “tophet” used by archaeologists who discovered the sites is borrowed from the name found in the Bible for a site outside Jerusalem. Note that in the follow passage Jeremiah seems to be indicating that child sacrifice was still happening near Jerusalem around 600 BCE.

Jeremiah 7:31-33: “And they built the high places of Topheth, which are in the Valley of Ben-Hinnom, to burn their sons and their daughters in fire, what I never charged them and what never came to My mind. Therefore, look, a time is coming said the Lord, when ‘Topheth’ shall no longe rbe said nor ‘Valley of Ben-innom’ but ‘Valley of the Killing,’ and they shall bury in Topheth until there is no room. And the carcasses of this people shall be food for the fowl of the heavens and for the beasts of the earth, with none to frighten them away.”

Aubet indicates that between 400 and 200 BCE some 20,000 (!) urns containing infant cremations were deposited in a tophet near Carthage. Some urns even contained the remains of as many as three different children. See p. 214.

Perhaps Elissa-Dido from Greco-Punic myth captures a political crisis in Tyre, where some of the aristocracy, led by a woman, headed out west as a way of ending the conflict, to a establish a “New City”—the literal meaning of “Carthage.” It is noteworthy that in the founding myth of Carthage Elissa throws herself into the fire in order to escape marriage to the native king.

The practice of polygamy, however, makes the choice of sons less damaging to reproductive success than the choice of daughters.

The son here seems to be offered as a substitute for the father. The very fact that sacrifice seems to have been so prominent among the elites seems to indicate that there was a widespread belief that it is the king, or the aristocraft, himself that should be offered for the good of the city. Frazer’s Golden Bough talks about sacred kingship this way. For a more updated take on this idea see Graeber and Sahlins in On Kings, who talk about the sacralization of kingship both as a way of legitimating royal sovereign as well as a way of constraining it. Sacred regicide would then be an extreme form of constraint implied by the king’s connection to the divine.

Ezekiel 20: 25-26. Bold and parenthesis added.

Yoreh’s position isn’t exactly “consensus” in the field, but I have been hard pressed to find serious takedowns of his work that call into question his scholarship, rather than merely disagreeing with his somewhat radical interpretation. On many matters relating to the ancient world we will simply never know the full truth.

Qtd. in Levenson p. 190.

They are, at least, playing a very different rhetorical game from the kind we normally play now. See my writing on rhetorical games here.

According to UNFPA, all of the rights are “[i]ndivisible and interdependent because all rights – political, civil, social, cultural and economic – are equal in importance and none can be fully enjoyed without the others.”