It has been interesting seeing the right adopt Foucault as a mentor on power, especially when there is such a strong tendency for non-academics to be dismissive of critical theory. Reading Foucault for the first time is probably in my top 20 or so most exciting reading experiences of my life. I had selected one of his first major works, History of Madness and went in unguided, essentially blind. I have previously tried to explain what I see as some common shortcomings in this genre of writing, using Foucault as a specific example.1 His writing seems to emit a strongly polarizing field, inspiring durable loyalties as well as hatreds. This post is an effort to explain why that is, and how it falls out of Foucault’s method.

Foucault attempts to bracket normative judgments around such common-sense notions as legitimacy in order to reshape how the reader understands certain historical developments. In order to short-circuit the natural, nearly automatic judgments that readers might make about what certain figures and events mean, he tells us in various ways that he wants to suspend certain ideological assumptions about the way the world is, and how it operates, in order to try on other descriptions that might ultimately be more convincing. Odd as it might sound, he also wants to suspend the question of whether the convincing is the same as the true. The effect of all this is to erase what Kenneth Burke calls “god-terms,” which give meaning and order to linguistic discourse, leaving unstable narratives that can be both highly useful and deeply unsettling.

In the first part I attempt to explain what Foucault does well, and why he is so influential, while outlining how the method he uses provides opportunities as well as poses problems. In the second part I explain what god-terms are. In the final part I argue that Foucault is polarizing because he commits deicide but is reluctant to confront the chaos that ensues.

As I mentioned in my previous post, Foucault’s “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History” (NGH) critiques “Whig history,” an attitude that sees history as a progression from the benighted past to an enlightened present.

Whig history seeks to explain how we moderns have broken from a “medieval” or “ancient” past by tracing how we got here from some primeval origin point in the deep past. It points out the events and great men who have lifted us up toward our present glory.2 The exemplary “Whig” historians of the 19th century also had a tendency to define “us” as a self-contained “Western civilization” that climbed up the ladder of progress by its own merits and virtues alone. From this perspective, a great civilization is like a seed that already contains the instruction set it needs to sprout and grow into a great mustard tree.3 It only needs resources from nature, as distinct from barbarians or other civilizations, in order to grow on its own.

In contrast to a search for a unitary origin, Foucault champions a method of “genealogy” that he adapts from Nietzsche. This produces a branching picture of networks and flows that comes to know “Civilization” as an abstraction—just a name for a porous network of metabolic loops, trade routes, migrations, cultural exchanges, and liminal spaces between cities and states.

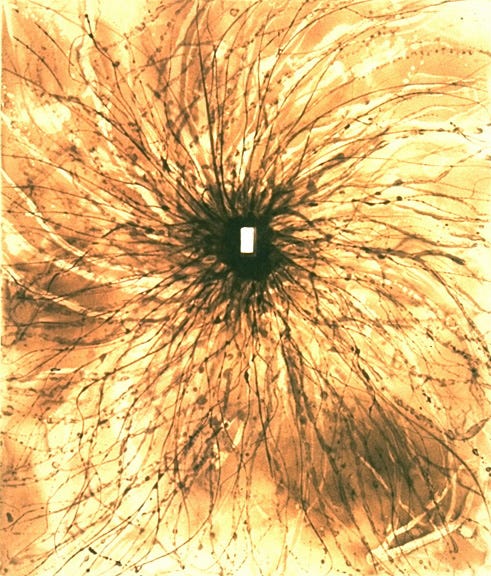

The “rhizome” was not one of Foucault’s concepts, but it is a better image, I think, for thinking about genealogy than the arborescent “family tree”, with all its orderly branches and clear lines of descent. Foucault was drawn to historical moments where civilizational circuits broke down, reversed, or changed course. While the Whig historian might have traditionally narrated these events as the result of political dramas starring national leaders, and the Marxist historian would tie events to class struggle dictated by the changing modes of production, Foucault instead traces the “capillary” action of daily life as it feeds into broader social currents.

An “event” like the spread of the insane asylum across northern Europe, for instance, is explained in very different ways. For the Whig, it might be explained by an enlightened ruler’s reading of Descartes and his decree to isolate, study, and treat the insane. A Marxist might see it as a method of disciplining labor by criminalizing the unproductive. Foucault, however, might point to seemingly arbitrary daily rituals inherited from late antiquity and how they fed into medieval monastic discourse. That monastic tradition, in turn, could have shaped patterns of thought in the 16th century that later migrated to newly emerging hospitals.

Foucault certainly sees the production of “docile bodies” as advantageous for states and employers, but rather than reducing it to a single driving force, such as capital, he sees it as the result of various small-scale influences distributed throughout society, including cultural attitudes, work organization, urbanization, hygiene, and religious practices.

For example, Foucault describes the “Great Confinement” of people newly considered “mentally ill” as shaped by:

the legacy of leprosy

changing attitudes about the divine and its connection to irrationality and madness — think mystery cults, prophecy, and mysticism

redefining “the human” away from one being in a divinely-ordained hierarchy of beings and towards a being privileged by its use of a narrowly defined “reason”

bourgeois status anxiety and its relation to changing moral norms

new ways of producing legitimate scientific knowledge

growing state power and its influence on the institutionalization of medicine

If you wanted to know why Foucault is the most widely cited author in the humanities, a little context helps. Our educational culture today has already deeply internalized much of what was novel and exciting about Foucault’s methods in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Writers, including academic historians, now almost unconsciously take “genealogical” considerations into account. Nor was Foucault alone in pushing historiography forward. The Annales School, for example, sought to write histories of the longue durée that captured the geographical rhythms of generations of people and the mentalities of everyday life. One could add Erving Goffman, Pierre Bourdieu, and plenty of others to the list.

Foucault, however, was the one who most elaborately theorized his methods, in works like The Order of Things and The Archaeology of Knowledge, and explicitly presented them as part of a critical assault on the “the humanities”—which had, by the ‘60s, become implicated in the chauvinistic nationalisms and catastrophic ideologies of the world wars. The final two paragraphs of The Order of Things, for example, say:

As the archaeology of our thought easily shows, man is an invention of recent date. And one perhaps nearing its end.

If those arrangements were to disappear as they appeared, if some event of which we can at the moment do no more than sense the possibility – without knowing either what its form will be or what it promises – were to cause them to crumble, as the ground of Classical thought did, at the end of the eighteenth century, then one can certainly wager that man would be erased, like a face drawn in sand at the edge of the sea.4

Again, context is everything. Without it, the first sentence here looks absurd. But Foucault is talking about a very particular conception of “man,” really a constellation of ideas interpellated by a relatively small set of canonical texts. It is not hard to notice, in 2025, that the male gender here stands in for the species. And the very fact that we notice the use of “man” instead of “human” is in some ways a demonstration of Foucault’s insight.

It is Foucault’s empirical contributions and insights that really cemented his status within the humanities. He and others provided a different way of doing historical research, which led to new ways of critiquing the so-called “modern” status quo. This was in some ways a movement away from an Enlightenment humanist tradition, critiqued by Adorno, Horkheimer, and others, leading some to call it “anti-humanist.” Liberal democracy, still engaged in a seemingly existential conflict with “communism,” was linked to the horrors of fascism, Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot through its Enlightenment heritage.

The genealogical method, therefore, sought to sidestep Cold War political battle lines by suspending the usual ideological frameworks entirely, using a move more typically found in phenomenology: bracketing or epoché. Foucault’s method often aims to be merely descriptive. The analysis of power suspends judgment on what is “good” or “bad” by putting questions about norms to the side. Norms, after all, are rooted in a community that finds itself in a particular time and place, and are therefore subject to change. The genealogical method is a historicist method that suspends questions of truth and falsity and instead asks how “truth” itself comes to be produced, and recognized as true, within particular societies, at particular times. Knowledge is identified with power.

As I’ve mentioned before, in my posts on “misinformation” and Plato’s Gorgias, truth is a tricky thing.

Its form of appearance very much does depend on a number of contingent factors, including not only the present discursive regime, but one’s position within it. The problem for Foucault is not that truth’s appearance varies, or even that we are in some ways blocked from ever seeing all the ways it might have appeared to long-dead people.5 Foucault understands all that and even tries to highlight it. The problem instead has to do with his use of epoché or bracketing.

Bracketing the normative is like pulling a block from the corner of Understanding’s tower. In normal circumstances, Understanding automatically supplies unstated context in order to make sense of what is being said. Most of those preexisting, culturally loaded assumptions remain out of sight and out of mind, despite being critical to producing the “sense” of the text. Pointing to a corner block and asking for its removal—asking for a suspension of judgment—can cause the whole structure to tremble. But it can also expose load-bearing concepts and relationships that were unconsciously taken for granted, as well as reveal different, perhaps better ways of rebuilding the tower.

At the risk of pushing this metaphor past its breaking point, we should now imagine not just a tower, but multiple, different structures in superposition. Understanding’s tower is kind of like the duck-rabbit optical illusion—when reading a text, its “meaning” isn’t just one thing, but rather a superposition of meanings, each composed of semantic blocks that are themselves in seething superposition. Now it looks one way; now another.

In clear communication, there tends to be a dominant sense secured by our shared sociocultural understanding, or what we might call a discursive regime . The goal of most language use is to transmit information that predictably impacts the world, as when we communicate in order to get someone else to “listen to us”—to change their behavior. Yet below the surface, there remains a turbulent, dynamic flux of meaning that, with the right prodding, can be activated to produce a different meaning.

The problem for critical theorists like Foucault is that even when a writer wants to suspend normative judgment, the words themselves cannot be endlessly restrained. The writer must choose certain terms in the course of writing, and those terms have meanings that inevitably exceed the writer’s chosen context. The terms are able to mean more and less than the writer intends only because they are already part of a discursive regime that gives them those meanings.6

The idea of a semantic tower also suggests a hierarchy of terms, with each concept connected by logical relationships that create a relatively stable structure of meaning.7 When a foundational term is removed or bracketed, such as a key normative assumption that colors the value of other terms and propositions, temporary supports may be needed to hold the structure up while the author explores the consequences of removing that term. This process can lead to valuable insights. However, such supports are not usually a permanent solution, requiring conscious effort to maintain, and the longer judgment remains suspended, the more unstable the entire structure becomes.

Permanent epoché is functionally equivalent to anomie, a normlessness that might threaten the integrity of the entire foundation. And it is a real threat. When readers approach critical theory writing, such as Foucault’s NGH, there can a temptation to resolve the instability generated quickly and simply. One way to do that is just to reject the bracketing outright—reject Foucault’s method and reject his conclusions without further consideration. A second way to do it is to immediately latch onto any available term in the text that might function as a new organizing, normative principle which can be used to build a new tower.

To better understand the stakes of Foucault’s method, we can turn to Kenneth Burke’s concept of logology. Kenneth Burke uses the term “logology” to describe the study of word-using. Just as theology is “words about God,” logology is “words about words.” Theology discusses the nature of God using words, and logology discusses the nature of words using words.

In his book, The Rhetoric of Religion, he argues that there is a deeper correspondence between theology and logology than you might expect between logology and any other -ology selected at random, like biology, or ecology, or archaeology. When we talk about the world, we do not merely reflect it; we add to it. Language creates an additional layer of meaning beyond the physical reality it names. This new symbolic dimension transcends the things to which those signs refer, and can therefore be used to refer to supernatural or preternatural things—the stuff of theology. As Burke points out, this also works in the reverse direction. Words originally used to refer to supernatural things, like the divinized agents that our prehistorical ancestors saw operating everywhere in the world around them, come to be used metaphorically in talk about everyday, ordinary stuff.

“Spirit” for example, moved analogically from its “natural” meaning as breath, to a word used to describe supernatural beings.8 The connotative meanings of the word, associated with living beings, evolved into new denotative meanings for marking things that seemed to have a will of their own, even if they didn’t “breathe.” The word could then move “backwards” so to speak, to the natural realm, to take on meanings associated with a real person’s character or temperament. There is a two-way road between the sacred and the profane, where words from the natural world can flow into the sacred register and then be re-borrowed back into natural language as a kind of double analogy.

For Burke, language is motive—it doesn’t simply convey ideas or formalize knowledge, it actively constructs the world around us, expressing and generating desires, identifications, and conflicts. Words even generate, almost of their own accord, a ghostly power that might otherwise be seen as unnatural: the possibility of negation. The idea of “nothing” doesn’t exist in the natural world as an empirical object. Nothing’s non-existence is only marked symbolically. Yet it functions as a kind of furnace of differentiation, perpetually generating new term, categories, and oppositions.

Negativity creates what Burke conceives of as a “linguistic drive towards a Title of Titles.”9 As language moves from the specific to the general, or from pointing out a specific tree over there to a category for “treeness,” it ends up creating a hierarchy of mutually implied negative terms. The category of “tree” also implies a category for all those things that are not a tree. The tree category can be enlarged to include a bunch of things that are related to trees, like “plants,” and that implies everything that is not a plant. This continues in an upward motion of generalization to produce a hierarchy of terms: trees, plants, living things. Eventually we get to categories like the “conditioned” or the “contingent,” which imply the “unconditioned,” the “necessary,” or the absolutely “free”—categories associated in theology with God, who, in at least some traditions, subsumes the categories of “Being” and “Non-Being.”

The logological equivalent of “God” becomes “god-term,” which is the title of titles for words that sit atop the terministic hierarchy, lending an almost sacred aura to the discourses they inhabit. And just as there is a two-way road for analogization between the sacred and the profane, god-terms are not just the result of the “upward” motion of linguistic generalization. All the sub-classes under a discursive god-term can be seen to “emanate” or “radiate” from it, (re)deriving meaning and salience from the god-term in a “downward” motion along the terministic hierarchy.10

For theology, God is literally the absolute source of meaning, from which every subordinate concept derives value. More mundane discourses might have multiple god-terms, or god-terms that are in tension or compete with the god-terms of overlapping discourses. Think of “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité.” Or the way that catholicity in Christian monotheism competes with an exclusionary secular patriotism.11

As an example, to illustrate, we can refer to Burke’s logological analysis of the book of Genesis, where he identifies three key terms: creation, covenant, and fall.12 Creation implies a creator who orders the cosmos. The covenant functions as the central god-term—a supreme title that sets the standard for divine authority and moral order. The ‘fall’ is implicated both in the idea of convenant (the possibility that it could be violated) and in the creation (the unity of the world was divided and ordered into parts that could now be at odds with one another). Together, these terms create a terministic hierarchy that drives a cyclical drama throughout the Hebrew Bible: God offers the Israelites a covenant, they sin, are punished, are called to repentance, and ultimately are reconciled. Language is motive; it not only records events but also actively shapes actions and values, ensuring that the deeds of biblical protagonists are always measured against this recurring pattern.

With that excursus on Burke out of the way, we can return to Foucault and his genealogical method of critique, which seeks to bracket questions about norms. The method makes no claims, for example, about the legitimacy of power. It therefore says nothing about the relative goodness or badness of liberal democracy, French absolutism, archaic Greek sexual mores, or the appearance of hospitals. Part of the reason for this is that norms themselves are fitted into the circuits of power, and so understanding those circuits requires getting clear of our own ideological lenses in order to see better how those circuits have changed over time.

What is meant by “legitimacy” for example? From within a democratic liberal framework, legitimacy is determined not only by votes (the democratic part), but by the sovereign’s guarantee of certain individual rights (the liberal part). Power flows top-down from the sovereign. It is associated mostly with the use of state power, since individual rights carve out an autonomous zone around each person making them free to contract with others. Illegitimate power in a liberal democracy involves breaking the law, and a ruler would be illegitimate if they seized power undemocratically or if they violated individual rights secured by law.

This liberal democratic concept of legitimacy is inadequate for a theoretical framework that sees power flowing through capillary networks at the lowest level of society to impact individuals in ways that have nothing to do with the sovereign’s exercise of legally delimited powers. Foucault requires us to think about the various rituals, practices, and institutions that govern the behaviors shaping our lives—including things like the “common sense” in our neighbors’, bosses’, and doctors’ heads. Part of his strategy for getting the reader to see how state power is connected to banal gossip and familiar social pressures is to suspend the distinction between the legitimate and the illegitimate in order to more expansively identify what he calls “power.”

Nancy Fraser has accused Foucault of “empirical insights and normative confusions.” She recognizes that “Foucault’s account of modern power constitutes good grounds for rejecting some fairly widespread strategic and political orientations and for adopting instead the standpoint of a ‘politics of everyday life.’” But she says that “Foucault’s work ends up, in effect, inviting questions that it is structurally unequipped to answer.”13

What is the structural deficiency? I think it’s a deficiency common to many critical theorists, not just Foucault, and follows from the indefinite suspension of normative judgment.

Critiques that bracket key norms effectively decapitate the terministic hierarchy. The whole point of suspending judgment is to free up a discursive web from the coercive influence of one or more god-terms. Theorists most succeed when they can show that a god-term has become more of an obstacle than an aid to thinking. Foucault’s success largely resides in how convincingly he showed a generation of scholars how much the Whiggish view of history, under the god-term of Progress, was missing. The essay NGH explains, in a sense, how he crossed that term out by moving from a search for “origins/Ursprung” to a search for “descent/Herkunft.” But he claims in NGH that genealogy doesn’t erect a new god-term in place of the old, because it is committed to the “systematic dissociation of identity”—which sounds very much like a dissociation of meaning. How far can one go holding judgment in abeyance? Even if one says they are committed to linguistic deicide, is it possible to keep the terministic apex vacant forever?

Nancy Fraser argues that Foucault is “in fact not normatively neutral.” Despite his pretensions to suspend judgment, his uses of phrases like “disciplinary society,” and “the carceral archipelago” are “rife […] with ominous overtones.” I have also argued that Foucault’s NGH undermines its seeming commitment to neutrality, and pointed to this quote as an example:

[I]t would be false to think that war exhausts itself in its own contradictions and ends by renouncing violence and submitting to civil laws. On the contrary, the law is a calculated and relentless pleasure, delight in the promised blood, which permits the perpetual instigation of new dominations and the staging of meticulously repeated scenes of violence […] Humanity does not gradually progress from combat to combat until it arrives at universal reciprocity, where the rule of law finally replaces warfare; humanity installs each of its violences in a system of rules and thus proceeds from domination to domination. (151).

Every author is free to be their own lexicographer. They can try to define what they mean when they use this particular word, and, by extension, what they don’t mean. Marx can tell us that by “Ausbeutung/exploitation” he only means something quite technical—the accumulation of surplus value by the employer paying for labor power. Foucault can tell us that when he refers to “power” or “domination” or “discipline” he is only referring to the dynamics of causal networks. But all these terms are inevitably embedded in contexts that exceed their own writing. Fraser thinks that to some extent Foucault is just confused about the normative implications of his writing. I think it is a little more complicated than that.

Discursive regimes don’t just describe truth for Foucault, they produce it, and the only really effective way to make that argument is to suspend the functioning of the god-term(s) in the discourses he is writing about. Blocking out the apex of the terministic hierarchy breaks the upward-and-downward chains of meaning, opening up possibilities for movement and revaluation of terms. But it also exposes the impossibility of total epoché. The biggest problem for Foucault is that, like Milton’s Lucifer, he launches an attack on God’s despotic order, but he never quite introduces a new order of his own.

By refusing to anchor his analysis in a new “god-term,” Foucault leaves his terministic hierarchy suspended, its apex vacant.14 This absence creates a discursive vacuum, one that becomes filled by the very terms his method seeks to demystify: “power,” “domination,” and the like. These concepts, though framed descriptively, inevitably function as devil terms because they are the only sufficiently high-powered terms to stabilize the structure long enough for others to draw conclusions and extend Foucault’s insights beyond the text. They are devil terms because they operate in a purely negative fashion as things to be avoided.

One might argue that something like “resistance” or “liberation” might play the role of god-term. But it’s hard to make a strong case that “resistance” is anything but a reaction to being governed by devil terms. “Liberation” is similarly empty,15 and never explicitly theorized by Foucault, who is rather more skeptical of it as a means of legitimating power.

By leaving the apex of terministic hierarchies open, he invites perpetual reinterpretation, ensuring his work’s adaptability.16 Yet the worst uses of Foucault are those which uncritically position themselves against his charismatic devil terms by adopting expansive, almost infinite commitments to something like “permanent resistance.” Being “against power” is a vacuous, incoherent position. Unfortunately, sometimes Foucault makes it hard to see any other option because of his commitment to a decapitated terministic hierarchy which is incapable of addressing the question of legitimacy.

As it happens, late in his life he does get around to trying to address this question. In The Courage of Truth, he discusses the ancient Greek concept of parrhesia—or truth-telling.17 Partly a late entry into his ongoing argument with Derrida, the lecture also looks to me like a way of trying to address his own dissatisfaction with the normative void at the heart of the genealogical project.

See the first post in this series:

For the 19th century exemplars of Whig history, it was almost always men.

Whig history, in other words, is secular theology.

Foucault had a fractious relationship with phenomenology and its chief heir, Jacques Derrida. Foucault’s relationship to Kant, who was ultimately wrong about the objectivity of his supposed a priori conditions for “reason”—as Einstein proves in demonstrating the curvature of space under gravity—is also complicated. We might say that Foucault was indebted to Kant for his missteps, but then attempted to show how Kant’s supposedly necessary preconditions for "reason” were actually contingent. Whether this defeats reason or bolsters it depends on one’s perspective.

The meaning of the written word is always deferred until its encounter with a reader, who must interpret it, and that meaning is reiterated again and again at each encounter, “always already” in a different form.

Poetry is perhaps the best illustration of this phenomenon. Pick a poem you’ve never read at random and read through it at normal reading speed. Then read it a second time. Or try Shakespeare. Usually, the second reading is obviously different.

“Stabilization” being a relative term of degree here.

Burke, The Rhetoric of Religion, p. 8.

The Rhetoric of Religion, p.25

We should note that terministic hierarchies are not fixed. Negativity implies an element of choice, and discourse is dynamically shaped by the words (and meanings) conveyed during the process of communication. Burke’s analysis of predestination in the writings of Augustine, and the various theological responses to it throughout the centuries show that Burke was aware that even the meaning of god-terms were subject to change or even inversion. Nonetheless, the point is that if you want to understand a discourse, asking what its god-terms are is a fairly direct route for crudely mapping the linguistic motives at play—how certain words take on connotative and denotative meanings laden with implied values in a logological universe ruled by a terministic godhead.

God-terms are similar to “empty” or “floating signifiers.”

The Rhetoric of Religion, chapter 3, starting on p. 172.

“Foucault on Power,” pp. 27-28, emphasis added. See her book, Unruly Practices.

Marx, by contrast, doesn’t do this: “A spectre is haunting Europe — the spectre of communism […] It is high time that Communists should openly, in the face of the whole world, publish their views, their aims, their tendencies, and meet this nursery tale of the Spectre of Communism with a manifesto of the party itself.”

The “negative freedom” of some versions of libertarianism suffers from similar defects—it is a curtain of a god-term behind which lies power-as-wealth. Libertarians abhor violence, but in a world where you can’t use physical violence to get what you want, negative freedom is only secured by wealth that can be used to pay/bribe others to do what you want.

Foucault apparently said in an interview: ‘I don’t write a book so that it will be the final word; I write a book so that other books are possible, not necessarily written by me’. As far as I can tell, those interviews haven’t been translated into English (yet).

Parrhesia might be thought of as a way to reconcile critique with terministic hierarchies. Truth-telling might only be possible within an ordered discursive regime of values that imbue its words with meaning, but it retains the option for redefining those terms. The Courage of Truth is not one of his more famous works. It took several years for the transcribed lecture to be edited and translated into English, and so hasn’t been as widely read. But it’s also, for lack of a better word, a bit more ‘conservative’ than his earlier work. By 1983-84 he had experienced firsthand the enchantments of California’s gay- and drug-cultures and was decades removed from his youthful involvement in explicitly Marxist political parties.