In Critical Theory Context is Everything

Reading Nietzsche through Foucault, for beginners and veterans alike.

Last time I discussed critical theory in broad strokes and suggested that Michel Foucault is often accused of having a “totalizing” theory of power that verges on dystopian. The world that Foucault writes about often looks strange and uninviting. Indeed, that’s part of his aim: to estrange the reader from their world by pointing out previously invisible features of it.

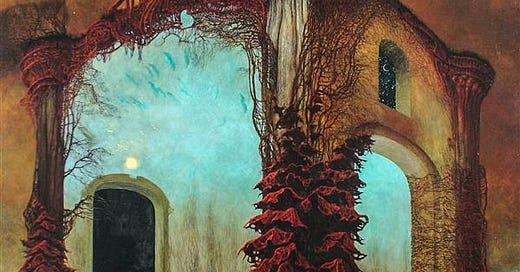

The typical critical move is double-sided, like a coin. On one side is a portrait of something that almost looks familiar, except for a menacing gargoyle in the corner or a strange fungoid growth matting the walls. On the reverse side is an inscription of liberty with the words “resistance” and “emancipatory logics.”1

In this post I will be looking a bit more closely at a particular example of critical theory: Foucault’s essay “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History”. While ostensibly about a method, it also offers a portrait of sorts. Our goal is to figure out what that portrait reveals and why the reverse is so faded.

First published in French in 1971, ten years after the completion of his doctoral thesis, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History” (NGH) elaborates Foucault’s evolving methods. During the ‘60s he had published several books including The Birth of the Clinic, still a prominent fixture in undergraduate and even medical school curricula, and The Order of Things, which cemented his status as a top French intellectual.

“NGH” is partly an extension of his earlier “archaeological” writings, which sought to describe the historical development of concepts like “madness” and “medicine” in Europe over say the last 500 years. This “archaeological” method was not an intellectual history, like the history of philosophy. Foucault instead sought to describe how these concepts were institutionalized in the “asylum” or the “clinic.” He further emphasized how much “institutionalization” was a two-way street. As the concepts evolved, they became the rational basis for establishing the institutions—they provided the reasons that the state should support these institutions. And as the institutions developed, the way that the people in charge of these institutions thought and talked about concepts like “madness” influenced how everyone else thought about it too.

Foucault is a “critical” theorist because he critiques a simplistic historical narrative which assumes that the present is the most enlightened, most rational, most moral period in history, and that progress will continue unabated into the future. By “digging up” neglected historical documents and artifacts, his writing presents a counter-history that attempts to trace how knowledge—for example, medical knowledge, that sorts the sick from the healthy and the sane from the insane—is often bound up with power over others. The institutional power to lock up the insane is derived from “power-knowledge” that sorts people into categories, with particular consequences.

Most importantly, for Foucault, we cannot take for granted the obviousness of these categories. In Madness and Civilization, for example, he argues that the very concept of “madness” emerged during a specific historical period, in specific places. Even the difference between the sane and the insane is specific to a particular historical milieu, and Foucault is interested in tracing how even what can appear to be an objective concept actually owes its shape and content to specific state, institutional, socio-cultural, and biological pressures.

As the title suggests, “NGH” reflects Foucault’s intellectual debt to Nietzsche, and is in many ways a prolonged meditation on how Nietzsche influenced Foucault’s approach to history. In that sense it is Foucault’s reinterpretation of Nietzsche for his present moment:

“For myself, I prefer to utilize the writers I like. The only valid tribute to thought such as Nietzsche’s is precisely to use it, to deform it, to make it groan and protest. And if then the commentators say that I am being faithful or unfaithful to Nietzsche, that is of absolutely no interest.”

-Power/Knowledge at p. 54

Also as the title suggests, “NGH” elaborates a genealogical approach to history that reflects an ongoing evolution in Foucault’s methodology.2 If his earlier “archaeological” works focused on discontinuities in discursive regimes—e.g. the emergence of “madness” in medical discourse, and how the representation of the “mad” or “insane” in language coincided with institutional changes as well as changes in the representation of “reason” in public discourse—then his “genealogical” works would emphasize how power-knowledge shapes material practices, disciplining people’s bodies and shaping their desires. They would also emphasize the dispersed, networked nature of historical causation, as well as sites of resistance, conflict, and contingency within that network.3

To take one example, from Discipline and Punish (1975), Foucault argues that the shift from public torture to imprisonment was not simply a result of “humane reform” argued for by Enlightenment moralists. The prison system developed alongside emerging factory systems and school systems aimed at producing “docile bodies” which could be comfortably slotted into economically productive labor roles. In fact, the moral argument really only becomes available to the moralists thanks to developments in surveillance and policing that suggest alternative ways of dealing with new forms of “delinquency” produced by the whole cultural package of networked actors.

“NGH” is a relatively short essay, though that doesn’t make it easy to read. It does offer a short window into what Foucault himself thought he was doing, however, and so can stand in as a mission statement of sorts for “Foucault” the author function, meant as shorthand for his entire oeuvre. If you want to know what people mean when they refer to “Foucault” as an exemplar of postmodern thought, you could do worse than reading “NGH.”

We run into a problem, however, as soon as the third sentence:

On this basis, it is obvious that Paul Rée was wrong to follow the English tendency in describing the history of morality in terms of a linear development—in reducing its entire history and genesis to an exclusive concern for utility.

The problem with “Foucault,” as with so much critical theory, is that context is scarce. “NGH” more or less assumes a familiarity with Nietzsche, including knowing that Nietzsche knew Paul Rée, and that On The Genealogy of Morals was partially a response to Rée’s theory on the evolution of altruism in humans.

A major reason that critical theory seems so impenetrable to many is that its texts are deeply embedded in arguments going back decades, if not centuries. Intertextuality and exophoric reference are practically hallmarks of the genre. Sadly, beginner guides and simple explainers can’t fix this problem, since they’re meant to be short and easy to grasp in isolation. The only way forward is to dive in and find our footing as best we can, chasing down half a dozen or more references to make sense of things. The more we read, the greater the context we can bring to bear on any text, and in time, the more meaning we’ll uncover in previously obscure details and footnotes.

So, the third sentence. It alerts us that Foucault is responding to a very old line of thought. He calls it an “English tendency” in history writing, or what some call Whig history—a form or mode of historical thought marked by the separation between the modern and the premodern, and that seeks to explain the victory of modern, liberal society by tracing its inevitable development back to some well-defined origin. We might instead call it an ideology. Despite claiming to be modern, and hence secular, it is rooted in a Christian eschatology that frames history as a march toward the Kingdom of God. Miracles have been superseded by scientific breakthroughs, which are no less miraculous in their own right.

Whig history is not limited to Englishmen. Even a radical like Karl Marx is Whiggish. One can find in his early philosophical writing a materialistic version of progress. By the time he and Engels have laid the groundwork for what would become orthodox dialectical materialism, the triumphant teleology is clear. Overcoming capitalism will lead to the withering away of the state and the end of such grubby things as politics forever. Everyone will be their own master in a new garden of Eden.

Yet anyone reading “NGH” in 2025 must be on guard—remember that it was published in 1971 and that its third sentence harkens back to the 19th century. It would be a mistake to think that everything that follows applies to history writing generally, that it might apply to that history book written last year or 50 years ago. Foucault in “NGH” is already 40 years behind Herbert Butterfield’s The Whig Interpretation of History from 1931. Edward Said would publish his seminal work on Orientalism in 1978.

The deadliest sin in critical theory is decontextualization. Critique is alluring because, at its best, it can spark a complete change in perspective. Žižek often likens it to the glasses in John Carpenter’s movie, They Live. After putting on a pair of sunglasses found in a dumpster, the protagonist suddenly sees the subliminal messaging in advertising spelled out clear as day. Also, some people are actually ghoulish aliens.

Sometimes when people read Freud for the first time they suddenly see the Oedipus complex everywhere. This generalizes to most critical theorists that are any good, particularly the “masters of suspicion.” And it is a good thing, I think, when readers find the material so compelling and want to test its limits—how far can we take this? when does it apply and when do we find it inadequate?

The deadliest sin in critical theory is decontextualization because unlicensed extension impugns the whole project. Lack of evidence, contentious premises, and unjustified conclusions make motions to dismiss easy.4 Yet so many critical theorists end up tempting their readers to commit that cardinal sin. Sometimes it’s because the author is a sloppy thinker. Other times it’s because critical insight requires a kind of blindness—think of how a shift in position closes down old lines of sight even as it opens up new ones.

Much of the time, however, it’s because the reader isn’t very careful. The reader is the one who doesn’t note, only three sentences in, that the essay is referring to a historiographical tradition more than a hundred years old. It may have things to tell us about the present. That is often why people write about old things. But if the author doesn’t make the connection between historical precedent and present circumstances clear, then the reader is still on the hook for justifying the extension of the argument.

If Whig history is a dusty antique, then why is Foucault writing about it? One answer is that Foucault is reinterpreting Nietzsche to describe his own method, and so takes as his starting point an historiographical tradition to which Nietzsche opposed his genealogical method. Another answer is that Whig history can be thought of as a tradition that still exerts a strong pull on history writing into the 20th century and beyond.

In “NGH” Foucault outlines an historical research program that would proceed from several important insights:

a “genealogical” method abandons the search for an origin (Ursprung) in order to trace a line of descent (Herkunft), because the search for the origin has always been impossible anyway, a metaphysical illusion

such a method would investigate how “truth” is inscribed “in the nervous system, in temperament, in the digestive apparatus”—it therefore turns away from the notion of history as the unfolding of an ideal towards history as the microdynamics of apperception, how concrete practices and the repetition of particular words shape beliefs and behaviors

rather than a historical narrative of great actors, it emphasizes points of “emergence” in what he calls “non-places”—there is an attention to the Brownian motion of history, and a recognition that tipping points are always contingent despite being in another stochastically overdetermined (i.e. no particular actor or place is either necessary or sufficient, forces ripple through human networks like waves)

it traces the reversible transformation of violence into law, and pays attention to what appears thinkable or sayable within different orders of living

there is no “outside” or “objective” view on history; all historiography emerges from and remains shaped by the concerns, questions, and limitations of the present

It is often difficult to determine precisely what Foucault means, simply because his writing here so often tends towards abstraction. Concrete references to things and events are sparing and often made in passing. They can be hard to decipher for the uninitiated, even though they tend to open up in the context of Nietzsche’s and Foucault’s entire bodies of work. On the whole, however, he presents a method that promises interesting ways of understanding historical and institutional development.

At the tail-end of the essay he provides three uses or modes of “historical sense” as understood within the genealogical perspective: the parodic, the dissociative, and the sacrificial. These modes mirror some of Nietzsche’s “uses” for “effective” history (wirkliche Historie), and it is here where Foucault is closest to making an intervention into history as a scholarly discipline. Today we might call it instead the “activist” moment in the essay—the point where Foucault lays out a call to arms.

It is in many ways the least important part of the essay, partly because its moment has passed, and partly because historians and non-historians alike have already internalized much of its programme.

Foucault, like many scholars, tends to write defensively, and is wary of opening himself up to criticism. Even the most careful writer, however, can’t escape the prisonhouse of language. Their words will inevitably suggest more than they mean.

I am interested in “NGH” because it is a convenient example of a short critical theory essay that tends towards the dystopic.5 Foucault doesn’t come out and say anything like “we live in hell and there is no escape.” The dystopic is more of a mood that settles over the essay largely as a result of the specific terms that Foucault uses. These quotes, for example, are illustrative:

[I]t would be false to think that war exhausts itself in its own contradictions and ends by renouncing violence and submitting to civil laws. On the contrary, the law is a calculated and relentless pleasure, delight in the promised blood, which permits the perpetual instigation of new dominations and the staging of meticulously repeated scenes of violence […] Humanity does not gradually progress from combat to combat until it arrives at universal reciprocity, where the rule of law finally replaces warfare; humanity installs each of its violences in a system of rules and thus proceeds from domination to domination. (151).

Nietzsche’s version of historical sense is explicit in its perspective and acknowledges its system of injustice (157).

These are delightfully provocative. They are also getting at something real and true. But when does pessimism shade into claustrophobic dystopia? Foucault never ends up referring to “justice” and seemingly has no explanation for why so many people seem to prefer rules and order to violence, whether or not law and violence are kin.

Shakespeare also presents a tragic view of human life and history, but his vision is counterbalanced by moments of profound joy, redemption, and human connection. In the next essay I’ll take a closer look at the rhetorical situation in “NGH” as a particular example of a tendency in critical theory to set up imbalanced terministic hierarchies—a hierarchy of terms dominated by one or a few god-terms that rhetorically structure the argument.

Check out that post here:

Even if “freedom” is too vulgar, too Confederate, one still wonders: why not “emancipation” instead?

It is possible to break up Foucault’s oeuvre into three periods: the “archaeological” in the ‘60s, the “genealogical” in the ‘70s, and the “ethical” in the ‘80s—the latter reflected best in his lectures at the Collège de France. Being spoken, the lectures are Foucault at his most readable.

Separating the “archaeological” from the “genealogical” in Foucault is really a matter of convenience, or a way of narrativizing his own changing self-conception. It is important to keep in mind that it describes a shift in tendencies and emphasis, not a sharp break.

This sometimes takes the form of motte-and-bailey style argumentation. As a practical matter, the record seems mixed on the rhetorical effectiveness of this technique. Sometimes the bailey can persuade because of its aggressive stance. The argument’s unhinged élan vital bullies the agreeable through shared pathos. When feelings cool, however, the bailey stands indefensible.

See my previous post for an explanation of what I mean by “dystopic” in this context.

Decontextualization in critical theory is a topic that fills me with a fair bit of alarm, because the nagging question that keeps coming back to me is, how do we know that the premises of so-and-sos argument aren't just completely made up? I'll look at scholarship, some of it by fairly big-name authors, that rests on some assumptions that I know are just plain wrong, based on firsthand sources in non-academic contexts. But how in the world do I prove that, when it's just a single analogy in a broader argument that's presumed to be basically factual in a theory that was written several decades ago?

Such a perspective inevitably results in presentism and orientalism, despite the fact that in theory (hoho) the whole point of critical theory is that it's supposed to work against such stereotypical analysis. I suspect this has a lot to do with how academia itself has become so alienated from the people it claims to serve. Latinx discourse is not the kind of thing that happens to anyone who regularly interacts with someone actually living in a contemporary context where it would be relevant, or not.

Is it unfair to believe that whilst the material is built upon a huge corpus of historically aware scholarship it is nonetheless badly written.

There is surely something to the old saw that if you can't write something clearly your own understanding is imperfect.

Furthermore impenetrable propose can serve as a shield for the writer from his own critical facilities and that of others.